‘Sailor’ versus “Zeiler”

I had originally written in the first sentence of the home page that “I … am a passionate sailor“. But that was problematic as that would be like a “Dutchism” (is there another term in English?). I cannot rightly call myself a sailor because that word applies to professional seamen, while for me it is an unpaid (on the contrary…) hobby. Even though that hobby started earlier, and is lasting longer, than most sailor jobs. In addition, sailors hardly work on sailing boats anymore.

In Dutch I would call myself a “zeiler”, which just means someone who sails, irrespective of whether it is a paid job (“zeil” = sail). ‘Sailor’ would best be translated into Dutch as “zeeman” (seaman). But how to translate “zeiler” into English? Not ‘sailer’ because that indicates a sailing vessel, or at any rate, never a person. Unless ‘Sailer’ is the person’s name of course which, as I learnt, does occur. Which I find rather strange because nobody in the Netherlands seems to have the name Sailing-boat or Ship. How to explain this?

Another mismatch – ‘on starboard tack’ = “over bakboord”

One example that instantly comes to mind is something that often confuses Dutch sailors(sic) when starting to work in English and vice versa:

Being ‘on starboard tack’ means a direction of the boat whereby the wind is coming in from starboard (the right side of a ship). According to the internationally agreed rules (the “COLREGs”) a sailing ship over starboard has right of way over one on port tack. When two sailing boats closely meet on a crossing course, Dutch sailors (sic) on the boat that is on starboard tack would however claim that right by shouting: “Bakboord!” – which means: ‘Port side!’ (left side of ship).

This is because the Dutch, in naming the tack, refer to the side that the sails and boom are out – which is always the lee side – and thus opposite from where the wind is coming, which is what the English refer to.

It is of course futile to argue about which usage is ‘right’ or better. It is just a choice, such as on what side of the road we drive, and as long as everyone follows the convention, everything will be alright. But is it?

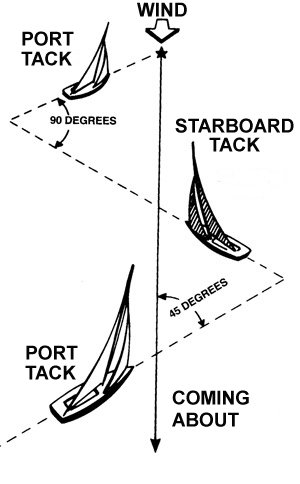

When making the mental switch to the English usage of starboard and port tack I found it quite illogical. When a sailboat is trying to reach a point directly to windward it will need to follow a zig-zag course as in this figure.

I find it more logical if ‘starboard tacks’ would move us to the starboard side of the destination and vice-versa. This is the case in Dutch usage. In English it is opposite.

Moreover, for ‘tacking to port’, we have to turn the bow to starboard!?

By the way (showing that I am not just being chauvinistic), driving on the left side of roads does make much more sense in combination with the general traffic rule that traffic coming from the right has right of way (which applies in both countries). That is why countries driving on the right had to create a special exception to the general rule for roundabouts: there the traffic coming from the left has right of way! In addition, when approaching a crossing with equally obstructed views to the left and right, from the left side of the road one has a much better view of what is coming from the right than on the European continent.

There are more confusing aspects between Dutch and English sailing terms, in spite of them probably having interacted a lot. It is generally held that “Starboard” and the Dutch “Stuurboord” have the same origin, which is more clear in the Dutch version as “stuur” means ‘steering’. On very old ships the position of the side-mounted, oar-like rudder was on the right side of the ship’s stern. The story is further that the person operating that rudder would have his back turned to the other side, so the Dutch say “Bakboord” for the port side. But… someone’s back is “rug” in Dutch, not bak! So the Dutch took “bak” from the English ‘back’? What a mess.

To be complete, ‘port’ is logically the side which those old boats were moored to when in port, in order not to damage the rudder.

The naming of wind and current directions

This is something that has been confusing to me even though in this case the English and Dutch (and more languages) are using the same convention. The wind is named after the direction from which it is coming while a current is named for the direction in which it is going. So, when a westerly wind is blowing over a westerly current, the forces are opposed to each other. I have not yet found an explanation for this anomaly and would be glad to hear if someone has a theory about that.

As an aside: “Wind against Tide”

By the way, it is quite scary for seafarers when the wind blows against a current. It makes the waves become dangerously high – much higher than when a wind blows over still-standing water with equal relative speed differences between the two media. With a constant wind the sea state can drastically, and within a very short time, change from perfectly smooth to very confused, even breaking, when a tide turns.

The reasons for this must be completely physically explainable but it took me a long time before I really understood it. I had been thinking: “how can the wind know whether the water is moving in respect to the ground or not? – only the relative difference in the speed between the water surface and the wind will determine the type of waves that this creates”. But experience shows this to be very different.

The solution was not to think of the actual, present, wind but about the already created waves (even in the form of a ‘swell’ – generated by a wind somewhere far away). When these existing waves meet a countercurrent (such as happens when the tide changes), their frequency and energy must remain the same, but their wavelength shortens, which is compensated by a higher amplitude (wave height) and a strongly increased steepness (see e.g. this source).