Hoek van Holland

Sailing has been my lifelong addiction. Not exactly sure when it started but very early. My childhood was in a coastal village in the Netherlands aptly named Hoek van Holland (“Hoek” means corner, not hook) because it is for three quarters surrounded by water. Right in the corner where the North Sea Coast is cut at a right angle by the large canal (the ‘New Waterway’) that connects Rotterdam with the sea. Rotterdam was long known as the biggest port in the world.

My father, grandfather, his father and related family were all professional sailors. Not on sailing boats of course, except for my great-grandfather whose portrait hang in my grandparent’s house and that I now carry with me on the Spirit. We were told little about him, except that he had been a ship’s carpenter in the navy (in Den Helder) and had died at a rather young age, when my grandfather was only 5 years old (in 1893).

The man’s staring eyes in that portrait fascinated me and I privately fantasised that when he had been sailing in far away, tropical, seas had been killed by a crocodile. The truth, as I learned later from my brother’s lovely account of our family’s history, was rather more mundane – he died from a lung infection (probably Tuberculosis) in 1893 in Vlissingen. His wife, Catharina van der Hoff, who further raised her six children alone while running a laundry shop might more truly have been a hero. But that’s not how a young boy’s romantic imagination worked at the time.

At home, my father always forcefully impressed on his four children and wife that his job was not a hobby but ‘damn hard work’. Yet, when we saw him in uniform at work he radiated quite something different. So, as a young boy I just knew that I would become a sailor like him. Until I was thirteen years old and had to start wearing glasses. My father told me that with bad eyes I could not become ‘stuurman’ (mate). My first big disappointment in life. I could still work on a ship of course, he said, but only, for instance, as an engineer, radio officer, steward or cook. But that did not sound like the real thing. I was fascinated to do the navigation – how to find your way to a small, far away, island when you cannot see any landmarks and wind and currents set you off.

Together with my best friend during primary school I built small wooden model boats that we tested in a pond. His father was a captain for the same shipping company where my father was first mate at that time, and I admired him much (even my father did, saying he was an excellent captain). He could tell fascinating stories but also was a great practical joker. Once, when he had American guests on board, he told them that the high towers they saw arising from far out at sea, when approaching the oil refineries at the outer harbours of Rotterdam, were “our space rockets”. This was at the time that the Americans were working hard to be the first country that brought humans to the moon, and they were genuinely shocked for some time.

ms Prinses Beatrix (1939 – 1968), the ship where my father was a first mate

One time, in secret, my friend and I built a big raft from drift wood and old ropes that we found under the large concrete jetty where our fathers’ big ship was moored in the New Waterway. It was exciting to sit on it and, while still attached to the piles with old but thick ropes, see the ebb current rushing under us. It was like we were moving fast! It is lucky that, while tempting sometimes, we never dared to throw loose the lines. The current would have swept us unstoppably past the piers and out onto the North Sea. When we went there a next time, the ropes had broken and the raft was gone.

At the end of the old northern pier in Hook of Holland was a light stand. On afternoons after school I sometimes went there and even climbed it, though forbidden. It had a railing all around and by sitting on the west side, right next to the big mist horns, you were surrounded by water for almost 360 degrees. There it was easy to imagine being on a ship plying the seas. That’s also were I secretly lighted my first pipe, at 15. Never sat there when it was misty though.

Inland I still feel more ‘locked-in’ than along a coast. Although on land you are in principle free to take steps in all possible directions, especially in Holland you are soon blocked by a highway, a building or barbed wire. The only inland places giving a similar feeling of freedom as at sea I later experienced in the wild spaces of the Serengeti planes in Tanzania, and far north in the mountains of Lapland.

I delved into all the study books from which my father had learned his trade at the Nautical School, on Seamanship, Navigation, Weather, etc. even before reading the classic adventure sailing books.

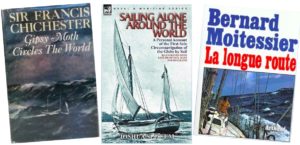

When I was 16 (in 1967) Sir Francis Chichester became my hero after his solo around the world journey with just one stop (in Sidney), seeing his picture in the newspapers and later reading his books. He was wearing glasses! Thereafter I read any sailing book that I could lay my hands on. Those of Joshua Slocum and Bertrand Moitessier becoming all-time favorites.

Vlissingen

Although no achievement from my side, I always felt a bit proud to have been born in Vlissingen in the far southwest of the country. It is perhaps the most maritime-feeling city and in a province consisting of islands embraced by big sea arms, aptly named Zeeland (‘Sea-land’). Even though my family moved to Hoek van Holland when I was only three months, we often stayed with my grand-parents in Vlissingen during summer holidays.

Even more exposed to the prevalent south-westerly winds than Hoek van Holland, the sea always felt very near in Vlissingen. During storms huge waves broke over the ‘boulevard’. This was in my youth reinforced through all senses by the loud bangs of steel hammers on steel coming from the big ship wharf “De Schelde”, of which the high cranes dominated the skyline from any point in town, and the smell of fish and shrimp from the fish market next to the fishing harbour (since long now turned into a marina).

My father had one brother, who also was a sailor, a sea pilot. But the extended family of his parents in Vlissingen was far more numerous and all the men were sailors or pilots and the women mostly married to sailors. My Uncle Pierre Marchand was, as we were told, a much beloved teacher in Seamanship at the Nautical School in Vlissingen. A gentle man with great natural charisma and a deep bass voice.

The family meetings in Vlissingen during birthdays celebrations were impressive. My grandparents then opened the sliding doors between the front saloon and their bedroom and arranged a long series of tables in the middle with chairs around it.

As a small boy aside I was listening with red ears to the yarns that those old sailors spun. It became ever more smoky, noisy and merry, fueled by the “borrels” of ‘Jenever’, Dutch gin. Many of the uncles had been working and sailing part of their life in the “Netherlands-Indies” – which only a decade before had become independent from the Netherlands as Indonesia. No doubt their stories also kindled a fascination for the tropics.

As an aside, I haste to add, I did not become an alcoholic. But smoking… alas still enjoy that addiction too much. But only the pipe, as my grandfather did, and my father during periods. Never cigarettes.

Manifold were of course the stories about “the War” – the second world war from 1940-45. But that’s a subject for other posts – I have all my life been an antimilitarist. Suffices to say here that I am happy none of my relatives, as far as I know, had been fighting as soldiers. One of the many uncles had served in the navy, but in an administrative function I believe.

My mother’s family were all landlubbers. Nevertheless, my mother loved sea travel, even before she met my father. Immediately after the liberation from the German occupation in 1945 my mother, who was 23 by then, fled to freedom by taking her first paid job as a shop servant on the most beautiful Dutch passenger ship ever, the ms Nieuw Amsterdam. She crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the USA, the Dutch Antilles in the Caribbean and Brazil. Hence, she completely understood my maritime interests. She also liked to read the sailing books that I devoured – while reminding me that she rather not see me go and do the same. However, she always supported her four children in whatever they wanted to do.

Sailing by the wind

The above may for a good deal explain where the love for the sea, ships and the tropics came from. But it can not yet explain the love for sailing– in the sense of being propelled by wind using sails. Motorboats interested me much less. In fact, at the young and impressible age of about six I was very scared when for the first time being shown the engine room on my father’s ship the ms “Prinses Beatrix” (not his ship of course).

While I was fascinated to see engines as big as houses, the noise, smell and enclosedness (no windows there!) terrified me. That was on the first trip with my father from Hook of Holland to Harwich during which I also got seasick, which neither instills love for seafaring.

When young I was especially afraid of loud noise. When I first heard the loud blast of the horn of the ship (just after departure, when the ship was preparing to turn around in the New Waterway) I cried so much, my mother told. After that they warned me in advance, so that I could cover my ears with my hands or something else. Not that it did much to reduce the sound, but psychologically it helped.

However, these early scares on the big ship did not hinder my fascination for all the other aspects on later trips. Such as looking through the big binoculars to see the first land appear at the other side of the sea: England! To be on the bridge and allowed a look at the compass in front of the big wooden steering wheel, or the green radar screen. The silent concentration on the bridge, only broken by course commands from the mate such as “Steady as she goes”, or a number, which were then repeated by the man at the wheel.

Unless it was very bad weather, it was fun to walk the stairs inside the ship. When the ship’s nose went down, you felt very light and could race up the stairs without effort, until it lifted again and you felt very heavy.

I actually first learned to sail when I was 12 or 13 at a sailing school during one summer holiday week on the Kager Lakes near Leiden, on a “16 kwadraat BM”. That opened a whole new world. I had already learned from books the names of the sails, spars and lines, like sheets, halyards, shrouds and stays. But now it was for real! You pulled the main sheet in a bit and when the wind filled the sail the boat would start to move. With more wind, you felt the pull of the tiller in your hand increase, the boat would start to heel a bit, and go faster and faster. Especially magic was how, by repeatedly tacking, you could reach any point upwind – going against the force that drove the boat!

But hey, why should I try to explain the attractiveness of sliding effortless through the water, and over waves, just by making use of the forces of wind and water, the panta rhei– everything-flows-feeling that every sailing fan already fully understands, and which those who do not like it would then still not understand? I write not to convert the latter as there are plenty of the former. And it does not really matter to which group one belongs.

Still, I like to find the best ways to describe it. But for that I must cite writers who did that far better than I ever could. A start of that can be found here.

Wat leuk, papa: je eigen website!! Veel liefs, Iris

Dank je Iris! Ik ben vereerd dat jij de allereerste bezoeker bent. 🙂

Liefs, Papa

Hoi Ron,

Erg leuk om te lezen en natuurlijk zeer herkenbaar. Er spreekt blijheid uit je manier van vertellen. Je kijkt met genoegen terug en dat heb ik ook. Alles wat nu verleden is uit onze jeugd is toch mooi om op terug te kijken. Niet alles natuurlijk maar wij mogen blij zijn dat het goede overheerst. Het kan zo anders zijn weten we nu. Het zou mooi zijn als er uiteindelijk toch een papieren versie van zou komen.

René

Beste Ron, min of meer toevallig ontdekte ik deze website. Woon je in Nederland of nog steeds in Azië?

Wij verkochten, na 32 jaar, de Heiltje en wonen sinds 2013 in Oegstgeest weer aan de wal – vanuit onze serre wel met uitzicht op het Oegstgeester Kanaal. Hartelijke groeten, Henk Dessens.