Preamble

Like (almost) everywhere in this personal website, my posts on books and music are not meant to persuade anyone reading it to join my opinion or views. Neither will my choice of post topics attempt to provide a comprehensive representation of my tastes in books and music. Not only would that be impossible but who would be interested in that? I myself am not. Google’s (Youtube) algorithms will know best I suppose, but only after I have gone, because as long as I live I will keep adding data.

I must acknowledge that, in spite of all the darker sides of the internet, Youtube has made it so incredibly easy to compare and enjoy different interpretations of musical pieces. A great joy to do that at ease at home. In the past, one had just about time to listen to some parts of two or three different versions in a CD shop. Then we took one CD home and that was then the version with which we became most acquainted; and rarely looked further. Without the internet I could obviously never have written this post.

In my music posts I will not write about how much I enjoy the works of Monteverdi, Purcell, Dowland, J.S. Bach, Händel, Mozart, Beethoven, Vivaldi, Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Bruckner, Brahms, Schubert, Rachmaninov, Chopin, Mahler, Prokofiev, Sibelius, Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, Vaughn Williams, Erik Satie, Steve Reich, John Cage, Arvo Pärt, Phillip Glass and so many more. Other people can do that much better and it is anyway better to listen to music than to write about it. I often combine it with writing, whatever the topic.

True, that list of composers already gave away my general preference: all what is broadly called ‘classical’ music. This has nothing to do with my age, I already loved classical music in my early youth. I also like some popular music but it has never affected me as deeply. Music associated with the Wiener ballrooms, such as Johann Strauss and Franz Lehar, as well as most kinds of Jazz, can very effectively be used to chase me far away.

So what will guide my choice of blog topics in books and music? There are no fixed rules but it will often depend on having discovered or experienced something that is perhaps not generally known. Or something that I found to be special that I like to study a bit deeper and share. Even if just to document it for myself, because writing is often a good way to think about and ‘research’ something.

This first post about music may illustrate this.

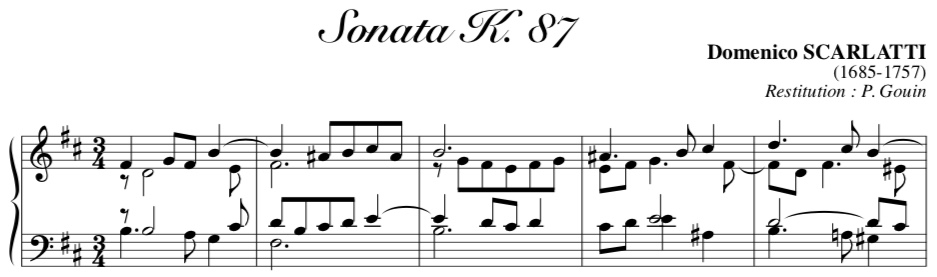

Domenico Scarlatti (1685 – 1757) is well-known for his sparkling keyboard Sonatas. I regularly like to listen to them, while comparing interpretations of different pianists. But the reason to write about this subject is because among the many Scarlatti sonatas there is one (Sonata in B minor, K.87 / L.33) that to my ears is different from all the others and in some mysterious way most completely resonates with my being.

I must relativate “all the others” because I have by far not yet heard all the 555(!) sonatas that Scarlatti has composed1 .

Other composers have certainly also created works that resonate with me as much, if not more. But I often wondered why this particular sonata for me transcends all the other most commonly played Scarlatti sonatas, while I have not yet heard or read anybody else noting anything special about K.87. It is not among the 15 most frequently played ones such as K.1, 8, 9, 11, 17, 27, 30, 39, 141, 146, 159, 380, 450, 466 and 531.

There is a range of famous and less well-known pianists with beautiful Scarlatti interpretations and I appreciate many of them. But, those who play Sonata No. K.87, usually play it too fast, and then it looses its special, favoured position for me. It is not a virtuoso piece- technically not difficult to play. Scarlatti did not indicate a tempo for this sonata – I think because its character self-evidently asks for it to be played slow, at most Adagio.

Mikhail Pletnev’s interpretation of K.87 thus far hits the bulls eye for me.

It takes Pletnev more than 7 minutes to play this while most others do it in around four minutes – even Horowitz. This translates into about 60 bpm (beats per minute). The other extreme can be found on a Wikipedia page, on a digital harpsichord, rushing it off in just over 2 minutes (200 bpm) – a Horror!

I certainly do not contend that Scarlatti’s sonatas in general are played too fast. On the contrary, many of them cry out for speed and if a pianist is able to go fast with perfect accuracy it does not feel rushed (hear for instance Michelangeli, or even faster by the wonderful, rising piano star Yuja Wang: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JH4oSkGh9uw).

Some pieces can be played in a range of tempi without detracting much from their pleasure. And pure musical pleasure is what characterizes most of Scarlatti’s sonatas. But K.87 is exceptionally serious, mournful even, some say. There is not a single tremolo or trill, which abound in almost all other sonatas. I find K.87 a ‘jewel’ – even though that is a bit strange to say because it is perhaps the least ‘sparkling’ among all the glittering Scarlatti sonatas.

But to my feeling it is not sad. More contemplative, like a ‘philosophy of life’. In spite of the deceptively simple score it has many layers. But to unveil and express those layers it must be played in a slow tempo.

Ivo Pogorelich (DG435 855-2)2 comes quite near with taking 6.15 minutes. As does one Spencer Myer (6.01). But neither is as good as Pletnev (7.05) in bringing out all layers of the piece.

While Scarlatti of course composed his sonatas for the in his time existing varieties of the harpsichord, many of them (imho) sound better on a modern grand piano. I tend to agree with Maarten ‘t Hart’s3 verdict of the harpsichord: “as if you drop a box of thumbtacks on the floor”. Yet, while writing about this I just discovered that the harpsichordist Scott Ross was the first to record all 555 sonatas. The handful of harpsichord renditions from him that are available on internet are certainly enjoyable.

Pletnev plays other sonatas also in his own particular and exciting way – and certainly not slower than others – but he does not in all sonatas surpass the renditions of, for instance, András Schiff, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Horowitz, Clara Haskill, Martha Argerich, Glenn Gould and Ivo Pogorelic. Also found some pianists whom I had never heard of who play Scarlatti beautifully such as Dubravka Tomsic (who uses ‘Helena Schubert’ as her artist name) and Yevgeni Sudbin.

These interpreters cannot be linearly ranked by even one person’s taste I think.4 While some play some sonatas ‘best’, others can excel in others. Sometimes this judgement can vary according to one’s mood, time of the day or season. But so far Pletnev and Pogorelic give me the ‘best’ interpretation of K.87 (at all times).

There are many quite useless discussions about personal taste and whether one or another version would be more “as intended by the composer”. Nobody can verify this, but it may well be that Pletnev’s version of K.87 is not as it originally sounded. So what? The fact remains that this version happens to totally resonate with me. And I only have me to enjoy music with.

The latter is not said jokingly – I do believe that ‘resonance’ is the correct term to use because it implies a precise matching between a sender and a receiver. Each of our minds+bodies forms a unique instrument with its own spectrum of eigen-frequencies that will resonate more with certain music and less, or not at all, with other pieces. And that will be as far as I can come to explain why this piece has that effect on me.

Does liking ‘sad’ music mean that I am a sad person? Once I ‘confessed’ to a school mate that I liked classical music better than pop and he retorted: “Oh why, that’s so sad!” That was in the early heydays of the Beatles and Rolling Stones and made me wonder: how come that sad music makes me more happy, while some kinds of happy music make me sad?

I was lucky to have three boyfriends at college who also ‘openly’ liked classical music. Two of them played the violin and the third one, my best friend during secondary school, liked to play the guitar. Although the latter especially loved technical things like repairing cars. Once he bought two old, broken Renault 4’s cheaply and turned them into one working car that, after using it during our summer holiday, could be sold for a good price. However, what is relevant here is that at his parents home they had a special music room, completely in Louis XIV style, with a good sound installation, many records and a pianola with a beautiful sound and many pianola rolls. There, after coming back from the workshop, we drank whisky on Saturday nights and, for instance, listened how Busoni may have played Liszt’s piano version of Paganini’s La Campanella5 – his ghost moving the pianola keys. But I digress.

The contrast between K.87 and many other Scarlatti sonatas is to some extent comparable to that between the slow middle movements and the faster opening and closing parts of Mozart’s piano concertos. The latter are often allegro to presto, jubilant, virtuoso and extravert, in stark contrast to the andante or adagio, melancholic, more introvert and more emotionally moving, middle part.

A striking example of how much the impact of certain music can be augmented by playing it much slower than usual was Reinbert de Leeuw’s version of Erik Satie’s ‘Gnossienes and Gymnopédies’. But that feat was applauded by many music lovers. I have thus far heard nobody else about Scarlatti’s K.87.

On the 2nd of May 2018 Spirit was hauled out of the water in Port Takola Marina near Krabi, Thailand. Her masts were taken off and a ‘shed’ was built over her because the rainy season was starting. The main purpose was to remove the old teak decks, leaking at several places, and replace it with epoxy and paint. Only the cockpit seats and deck over the rear cabin get new teak, to keep something of the original look and avoid a bath-tube like cockpit.

On the 2nd of May 2018 Spirit was hauled out of the water in Port Takola Marina near Krabi, Thailand. Her masts were taken off and a ‘shed’ was built over her because the rainy season was starting. The main purpose was to remove the old teak decks, leaking at several places, and replace it with epoxy and paint. Only the cockpit seats and deck over the rear cabin get new teak, to keep something of the original look and avoid a bath-tube like cockpit.

The caulking was brought in the seams after priming and then left at least two weeks for drying before cutting/ equalizing- to prevent it shrinkage.

The caulking was brought in the seams after priming and then left at least two weeks for drying before cutting/ equalizing- to prevent it shrinkage.