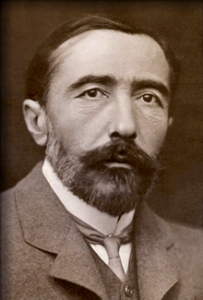

Joseph Conrad is my dearest novel writer. “Nigger of the Narcissus” was the first book I read of him when I was about 18 years old and it hooked me. Over the years I read all his other books, many twice and some thrice. And, once my Spirit1 is floating again – exactly in the waters where many of his stories were set to play – I have promised myself to read them again; slowly sipping them like a good wine.

The first reading was often quick because the stories were too captivating to allow time for looking up the meaning of the many, new to me, English words. Especially adverbs and verbs – an incredible vocabulary for someone who was born in Poland, after that first learned French and only later in life English. There was more time for keeping the dictionary at hand when reading a book the second time, when already knowing how the plot would evolve.

Even though his novels can be as thrilling as a detective, the storyline can be held up by page-long descriptions of the surrounding scenery. These are often about a landscape and nature – including the weather, as is to be expected from a sailor- but they can also be descriptions of a human or other phenomena. Slowly cherishing those sections was the best part of second readings. Here an arbitrary example, taken from “Nostromo”, describing a day, from dawn to night, as could be seen from the deck of a ship for anchor in a bay somewhere in South America:

“On crossing the imaginary line drawn from Punta Mala to Azuera the ships from Europe bound to Sulaco lose at once the strong breezes of the ocean. They become the prey of capricious airs that play with them for thirty hours at a stretch sometimes. Before them the head of the calm gulf is filled on most days of the year by a great body of motionless and opaque clouds. On the rare clear mornings another shadow is cast upon the sweep of the gulf.

The dawn breaks high behind the towering and serrated wall of the Cordillera, a clear-cut vision of dark peaks rearing their steep slopes on a lofty pedestal of forest rising from the very edge of the shore. Amongst them the white head of Higuerota rises majestically upon the blue. Bare clusters of enormous rocks sprinkle with tiny black dots the smooth dome of snow.

Then, as the midday sun withdraws from the gulf the shadow of the mountains, the clouds begin to roll out of the lower valleys. They swathe in sombre tatters the naked crags of precipices above the wooded slopes, hide the peaks, smoke in stormy trails across the snows of Higuerota. The Cordillera is gone from you as if it had dissolved itself into great piles of grey and black vapours that travel out slowly to seaward and vanish into thin air all along the front before the blazing heat of the day. The wasting edge of the cloud-bank always strives for, but seldom wins, the middle of the gulf. The sun—as the sailors say—is eating it up. Unless perchance a sombre thunder-head breaks away from the main body to career all over the gulf till it escapes into the offing beyond Azuera, where it bursts suddenly into flame and crashes like a sinster pirate-ship of the air, hove-to above the horizon, engaging the sea.

At night the body of clouds advancing higher up the sky smothers the whole quiet gulf below with an impenetrable darkness, in which the sound of the falling showers can be heard beginning and ceasing abruptly—now here, now there. Indeed, these cloudy nights are proverbial with the seamen along the whole west coast of a great continent. Sky, land, and sea disappear together out of the world when the Placido—as the saying is—goes to sleep under its black poncho. The few stars left below the seaward frown of the vault shine feebly as into the mouth of a black cavern. In its vastness your ship floats unseen under your feet, her sails flutter invisible above your head. The eye of God Himself—they add with grim profanity—could not find out what work a man’s hand is doing in there; and you would be free to call the devil to your aid with impunity if even his malice were not defeated by such a blind darkness.”

I do not know how this works on other readers but I find it magically evocative. As if we stand next to him looking pensively from the deck of the ship. We compose the picture (or rather, a time-lapse video) in our own mind by reading his. Old-fashioned for some perhaps, timeless to me.

The relation with my life’s main themes will be obvious. But there is so much more to find in Conrad – a subject for future posts.

Footnotes

- The name “Spirit” was inherited from the previous owners of my ship and there are indications that in the past it was named the “Spirit of .. {some geographic location}”. I once thought to make it “Spirit of Conrad”. I probably would if that would make it unique but another sailing boat has that name already. So, while there are many called just ‘Spirit’, it is most practical to keep the name short and strong. Easier to spell in the nautical alphabet too: Sierra-Papa-India-Romeo-India-Tango.